All Captains in International Cricket Are Equally Good

And Have Always Been In The Modern Era. This applies to T20s and Tests Alike

On October 26, 2008, Ian Chappell made the case for Mahendra Singh Dhoni to be appointed as the full time Indian Test captain even before India’s home Test series against Australia was complete. Anil Kumble was the Indian Test captain at the time. Dhoni had led India for a session or so during the Bangalore Test while Kumble was off the field, and Chappell had noticed “a team that looked far superior to the one that performed in pedestrian mode a few hours later when the appointed captain was back in charge.”

Kumble missed the 2nd Test at Mohali due to an injury, and Dhoni was asked to stand in. Chappell noticed a sea change in the way India played. Dhoni, in Chappell’s eyes, “went on the offensive from the moment he won the toss”, “created an atmosphere where the players enjoyed the contest”, and “had a smile from start to finish, enjoying his team-mates' success and revelling in the fact that India was playing an aggressive brand of cricket”. Dhoni was “wise to involve his team in an exciting contest where victory is sought from the first ball, because it galvanises the better players in his team”.

It is impossible to know or to show whether any of this is actually true, not because there’s nobody who can tell us if it is true (all the individuals mentioned in the above paragraph are alive and could be asked), but because the claims are not falsifiable. As Chappell himself put it, rather bizarrely, in the concluding paragraph of that recommendation letter for Dhoni to replace Kumble as India’s Test captain, “good captaincy is like pornography - it's hard to define but you know it when you see it.”

Mahendra Singh Dhoni went on to have an unexceptional record as Indian Test captain. Under his leadership, India were successful at home, and unsuccessful abroad. Their only away series wins came in New Zealand in 2009 and West Indies in 2011. Their fortunes fluctuated, as the fortunes of Test teams tend to do, with the quality of bowling available to them.

With ball by ball records, it is actually possible to measure the effects of a captain’s decisions. The basic decision a captain has to make is who to bowl from which end, to what field. Data on field placings remains a huge gap in the publicly available record of cricket matches, but the consequences of field placings - the runs conceded and wickets taken - are available.

For example, under MS Dhoni’s captaincy over 26 Tests outside Asia, Indian bowlers delivered 982 spells with an average length of 25.2 balls per spell. Of these, 72% were wicketless spells. The spells which followed these wicketless spells were also wicketless 72% of the time.

In 27 Tests outside Asia under Virat Kohli’s captaincy, Indian bowlers delivered 963 spells, of which 67% were wicketless. The spells which followed these wicketless spells were wicketless 66%.

As the charts below show, all five Indian captains in the list below made equally good or bad bowling changes. Whether a bowling change resulted in a wicket has to do with the conditions, quality of bowler, and how well suited the bowler is to the conditions. No captain was able to influence a Test match with a bowling change. Sure, some bowling changes worked and others didn’t, but the point is, that for each captain, they worked at about the same rate, and this rate was determined by the average quality of bowling for the conditions at hand at their disposal. So the fact that one bowling change happened to work for one of these captains tells us nothing about their “captaincy”. It is not evidence of exceptional judgment on that captain’s part. This pattern holds for every captain in the last 20 years who led in at least 30 Tests.

Wicketless spells are followed by wicketless spells at about the same rate. The effect of captaincy in Test cricket is trivial. This does not mean that captaincy does not matter. Rather, it means that in the professional era, the standard of cricket is so high, and the teams are so well known to each other, and batting and bowling occurs at the very cutting edge of ability in Test cricket, that there aren’t any efficiencies available through an individual who can read the game better than his peers and do something about it.

For example, there’s not much Joe Root could do about the fact that his off-spinner could not hold his length well enough to keep the runs down against India in England. Root did the only thing he could do - he bowled Moeen less. He was criticized for this by various former England captains who observed that England’s weary fast men were delivering the “spinners overs” as India piled up 466 in the 3rd innings at the Oval. Root did not forget that Moeen was available. He worried (with very good reason), that Moeen would not offer him the control he wanted.

Unlike batting and bowling, where better batters score more runs per dismissal, and better bowlers take cheaper wickets, there is no such thing as a better or worse Test captain. All Test captains are equally good. This could be extended even more generally. Any player who has been on the Test circuit long enough to know it well, would be as good at the Test captaincy provided they wanted to do the job. There are only two reasons for changing the Test captain in any reasonably good Test team. The first is that the incumbent captain no longer wants to do the job. The second is that the incumbent captain no longer commands a spot in the playing eleven as batter, keeper or bowler.

India have sacked one captain in the last 20 years, after tossing the job back and forth between Mohammed Azharuddin and Sachin Tendulkar between 1996 and 2000. Sourav Ganguly was sacked in 2005 because he no longer commanded a spot in the eleven as a batter. Rahul Dravid resigned in 2007 after India won in England for reasons which will probably only really become known if he ever writes a memoir. Anil Kumble retired from Test cricket after the 3rd Test against Australia at the Ferozshah Kotla in 2008 (he was captain of India at the time). MS Dhoni retired from Test captaincy and Test cricket after the Melbourne Test in December 2014. In those 20 years, India have become the best team in the world. This is, in no small part, because the BCCI has ignored the noise and not bothered with the circus of sacking captains after every series defeat (and there have been a few of those).

The Test captain is essentially a clerk. If this description offends white-collar sensibilities, let’s say that the Test captain is essentially a civil servant. The quality of the team depends on the mountains of work done by hundreds, if not thousands of other people over several years. It is they who determine the essential quality. The tactical options are similarly shaped by analysts who systematically record every action and provide a coherent picture of the competition. How often a team wins depends on the quality of the ingredients available to the Test captain. All Test captains are essentially as good at selecting ingredients as their peers.

If captaincy is a mirage, why is it such an alluring mirage? Why does the cricketing commentariat speak of it so much? I think they do it precisely because any claim about captaincy is essentially unfalsifiable. It invariably involves mindreading and a study of body language - two areas where one can say pretty much what one likes without it being possible for anyone to examine whether one is right or wrong. If one says something about batting or bowling, it is possible to examine the claim through the record. Captaincy, not so much. Cricket’s audience is also sympathetic to tales of “courageous leadership” and “inspired decisions”. Of inflexion points, pivots and alchemies made possible by exceptional men. This is the sort of stuff which is easier to inhale than it is to read.

The true story of cricket is that body language tells you absolutely nothing about a player. When Virat Kohli left the Indian team after the 1st Test in Australia (in which he scored a magnificent 70), Ajinkya Rahane, a figure who has the body language of a refrigerator, apparently cast the Indian squad in his own image in a matter of hours and led India to a thrilling 2-1 series win. Kohli was back in England with the body language of a cat on a hot tin roof, and did the same thing! Cricket is about batting and bowling, and it can be (and is) played exquisitely by curmudgeons and optimists alike. Trying to evaluate the body language of a complete stranger on TV, or worse, attempting to read their mind is not psychology, but psychobabble.

This is even truer in the T20 game. These short matches enable weaker teams to beat stronger teams more often than the longer matches do. The mathematical reason for this is that over 120 balls, the effect of a small number of unlikely outcomes carries greater weight than it does over 300 balls, and especially, over 5 days. This means that “captaincy” matters even less in T20 than it does in the longer formats, not more. It also means that tactics are shaped even more comprehensively by the backroom staff which collects a systematic record of all the available action to discern patterns - find favorable match-ups for their players, identify strong and weak scoring zones of opposition players, identify which lines and lengths ought to be bowled to which fields to which batter, and so on. Whatever occurs on the field is shaped by this information.

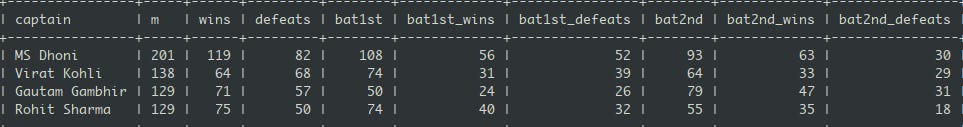

As I write this, MS Dhoni has led in 201 IPL games, won 119 and lost 82. Batting first, his record as captain reads 56 wins and 52 defeats. Batting second, it reads 63 wins and 30 defeats. Now, does this mean that Dhoni simply loses his ability to gauge the pitch and what a good score is, and how much to attack and how often to defend runs when he’s defending a total rather than setting a target? The pattern holds for all four captains (Kohli, Gautam Gambhir and Rohit Sharma) who have led in at least 100 IPL games. They all do better in run chases than they do defending totals.

After the 2021 Indian Premier League final, the journalist Abhishek Mukherjee conducted two polls on twitter, within a minute of each other, each lasting an hour. One asked whether Chennai Super Kings would have won the 2021 IPL without Dhoni. The other asked whether the Kolkata Knight Riders would have reached the 2021 IPL final without Eoin Morgan. There were 28% Yes votes in Dhoni’s case, and 68% Yes votes in Morgan’s. I repeated these polls in the same way, but ran them for 3 hours each. There were 73% Yes votes for Morgan and 42% Yes votes for Dhoni. The evidence points to the idea that captain Dhoni was indispensable to CSK, while captain Morgan was entirely dispensable to KKR.

A captain has to decide who bowls from each end at the end of each over. Morgan averaged 13.4 changes per match, while Dhoni averaged 11.4. KKR conceded 10 runs less than CSK per 120 balls bowled. The new bowler conceded more than 12 runs per over in his spell in 12% of Morgan’s changes, 15% of Dhoni’s. The bowling changes by both produced breakthroughs 20% of the time. Morgan’s bowling change slowed the scoring 42% of the time, to 37% of the time for Dhoni.

At the very least, there is nothing to suggest that Dhoni made better decisions than Morgan in the field. In anything, Morgan seems to have made marginally more productive decisions, though this might be explained simply by the fact that Morgan had bowlers better suited to the pitches, or that the pitches KKR played on were, on the whole, less suited to big scores. This is also evident from the batting side of things. KKR played false shots more frequently than CSK, and either lacked power, or faced less friendly conditions. Morgan made 12/133 from 139 in 16 visits to the crease in the tournament. Dhoni made 7/114 in 107 balls in 11 visits to the crease in the tournament. Dhoni’s average contribution with the bat was 10.4 runs in 9.7 balls faced. Morgan’s was 8.3 runs in 8.7 balls faced. Neither had a particularly good time of it.

If we consider all the decisions Morgan and Dhoni made in the field, there’s nothing to suggest that Dhoni’s decisions were better than Morgan’s. CSK had a better tournament because they had enough hitters in good form. In the 2020 edition of the IPL, they didn’t. Captaincy in T20 remains clerical.

And yet, as the poll results above and observations like this one by eminent observers like Harsha Bhogle show, there is substantial belief among observers of the game that the identity of the captain and individual decisions by captains matter in the international game. It is unlikely that chatter about captaincy will go away unless there is a revolution in the availability of detailed records and an improved capacity to present them. Captaincy will remain a hot topic of conversation in cricket - an escape within an escape - because it is easier to talk about than batting or bowling.