Harry Brook’s dismissal (see at 2 mins here, or see the picture below), and other English dismissals have been seen in the newspapers as “brainless”, “reckless” (and other similar words). Michael Vaughan, the former England captain wrote of Bazball

“It's silly, it's stupid, and it won't have constant success.”

The reporter Vithushan Ethantharajah observed that

“They will say they've played *this* way since the start of last summer, but that's bollocks and should be treated as such #Ashes”

Now, he may well be joking. One can never been sure. All these other ex-players and reporters know better than to respond as they have. They know as well as you and me that England have played exactly the same way against Australia as they did against all their other opponents since June 1, 2022.

It’s worth thinking about why the reaction has been this way. Perhaps these professional observers feel the need to reflect what they think are their viewers/readers feelings in the moment. In other words, instead of observing the game and reporting what they have watched, these professional observers are saying what they think their audience feels in the moment. Perhaps it makes better business sense to do this rather than to tell the public what happened on the field. Just read the BBC’s Chief Cricket Writer’s view here.

So, what happened on the field?

Run scoring in Test cricket involves taking risks. The bowling is usually too good to allow otherwise. If a batter waits for the bad ball to score, runs will be scored very slowly. A risk, by definition, comes with a non-trivial downside.

Where does the risk come from for a batter in a Test match? It comes, especially when attempting a scoring shot, from having to commit early to where he thinks the ball will arrive. Readers will note immediately here that making this commitment early leaves the batter vulnerable to any deviation or other misbehaviour (swing, extra bounce, less bounce, seam movement or turn) which occurs after the batter has committed to where he thinks the ball will arrive. Taken to its extreme, committing early can occur before the ball is released. This occasionally does occur, though it is extremely rare. When it does, it is called premeditation.

With this idea (the batter having to commit to where the ball will arrive) in mind, we can classify lines, lengths and conditions. Readers will note that when the ball is seaming or turning, such early committment is riskier than it would be if the ball wasn’t seaming or turning. Readers will also note that with short balls or half volleys, there’s either a lot of time after the ball pitches, or not enough distance after it pitches for the batter’s to be defeated.

The thing is, that in Test cricket, especially recently, its rare for bowlers to bowl long hops or half volleys. Change bowling is better than it is ever been in Tests. So, there has to be some early commitment to score runs. Some players have “scoring areas” - that is, they are more likely to commit early if the ball appears to be in certain areas. Virat Kohli for example, scores a lot of runs through cover, especially off the front foot. Consequently, you’ll see him driving outside off stump even when its not a half-volley. Usman Khawaja on the other hand, rarely drives on the front foot (unless it is a rank half-volley). He prefers to sit on the back foot and pull anything which is short of a length, even if it is outside off stump.

The intuition behind Bazball is that given that this early commitment is required to score runs anyway, why not do it often and score quickly? In other words, why not concede a higher chance of dismissal in exchange for quicker runs? This is the chance England take in Bazball (as do Travis Head and Rishabh Pant). It’s a good idea for England to play that way because they currently have a lot of players who can play that way.

It has worked for England. The wickets have been flatter. The ball has gone soft troublingly early in England and had to be changed often in 2022 and 2023, leading the perceptive English commentator Daniel Norcross to observe that these have been seasons of a “new ball ball”. Serendipitously for England, the conditions have become less hostile to batting just as they have resorted to Bazball.

What does “worked” mean here? England’s innings has lasted less than 80 overs in 22 out of 28 of their innings in the Bazball era. They have been bowled out in less than 80 overs in 12 out of these 22 innings. They’ve scored quicker and scored enough runs.

The thing with risk is that it comes off only some of the time. Here are some examples of when it came off for England in their first Test in New Zealand recently:

1. Ollie Pope stepping out to Matt Henry. He gets four for this. But everything is wrong here. His head is well outside the line of the ball, he’s falling over, he’s on the move. But, he doesn’t miss the ball. The point though, is that none of this is noticed, or if it is noticed, pointed out, by commentators or observers either live or at the end of the day. The only reason for this, is that ENG ended the day in a good position.

2. Pope’s second boundary. Again, he has stepped out and committed to the drive on the rise. The picture captures the moment just before he meets the ball. The new ball was seaming in the first hour that day. Pope could not possibly be sure that the ball wouldn’t seam enough to be half an inch to the left of where it appears in this picture. Pope connected, got four. He took a chance which came off.

3. Pope’s dismissal. It’s a good length, it moves off the seam. Pope is beaten by the movement. The ball takes the edge and goes to third slip.

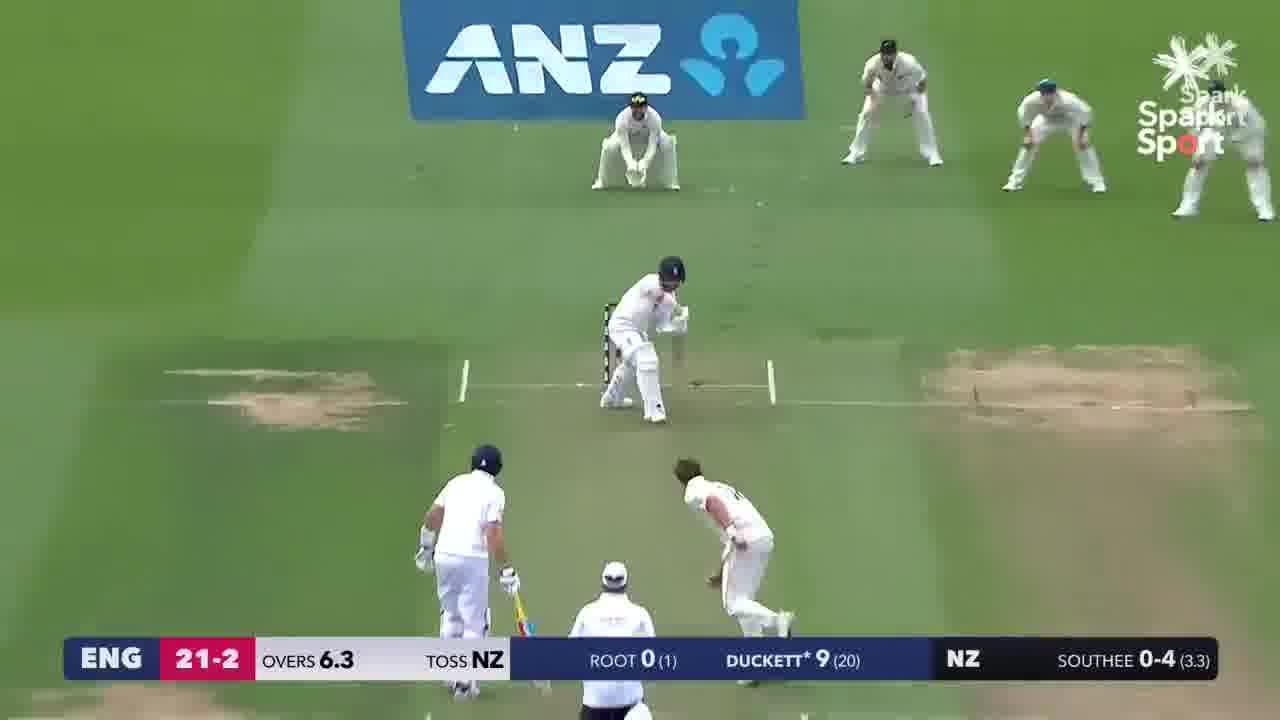

4. Duckett’s dismissal. He’s driving on the rise in the 7th over of the morning. He can’t know how much the ball is going to move off its original line after pitching. But he has committed to the shot. A great diving catch at third slip.

5. Brook arrives. His first boundary is conventionally streaky. He’s squared up and beaten by the outward movement off the pitch. Ball goes between slip and gully.

6. Brook’s second boundary. A square drive, on the rise, outside off stump. Again, Brook can’t know how much the ball is going to move, but he’s committed to the stroke. It comes off.

7. Brooks third boundary. This one is short and wide. It is a bad ball. He’s hit to the boundary. Now, conventionally, most openers wait for this type of line and length to hit. But as we’ve seen above, the English batters don’t wait for the bad ball under Bazball.

8. Brook’s fourth boundary. He has stepped out, just like Pope, and the ball flies airily past cover-point. The gaps are huge in Test cricket.

9. Brook’s 8th boundary. It’s the 23rd over now. And Brook’s backed away to leg. He scores four. Where do you think the ball goes? The score is 86/3. Root isn’t playing Bazball. Would it have been brainless/reckless/stupid if Brook had miscued this and it had gone to hand?

Note that these are just the boundaries from the highlights reel. This does not include all the misses or miscues. Take every English batting innings since June 1, 2022, and you will regularly find examples of this. It is not, as Stephan Shemilt says, that England have lost the ability to read the room. It’s not even as though England’s batting has struggled in this Ashes series. They have scored 393, 273 and 325 in their three innings in the series so far.

England’s problem has been their bowling. Just as Bazball has been of little competitive significance to England’s run of Test successes leading up to the Ashes (they have been winning because they’ve been table to take 20 wickets), it has been of little competitive significance in these Ashes. Consider the first three innings in the series for England and Australia in the 2023 Ashes. Over these six innings, England have averaged a false shot every 5.0 balls, and scored 3.7 runs per false shot. Australia have averaged a false shot every 6.1 balls, and scored 3.9 runs per false shot.

In Pakistan, England’s bowlers induced a false shot every 8.8 balls, and Pakistan’s batters managed 4.9 runs per false shot. Pakistan’s bowlers induced a false shot every 6.3 balls, and England’s batters managed 5.8 runs per false shot. England came out ahead on the runs per false shot even though their batters played false shots more frequently. The England bowlers managed 60 wickets in three Tests.

Similarly, in New Zealand, England’s batters managed 4.3 runs per false shot, while England’s bowlers conceded only 3.3 runs per false shot. England came out ahead, even though England’s batters played false shots more frequently.

Even in England, taken as a whole (starting on June 1, 2022, and ending on Day 3 of the 2nd Ashes Test), England’s batters have managed 3.5 runs per false shot and England’s bowlers have conceded 2.9 runs per false shot, even though, England’s batters have played a false shot every 4.5 balls, to one every 5.1 balls by visiting batters.

Until these Ashes, Bazball has “worked” only because England’s bowlers have been able to take 20 wickets. In these Ashes, things have changed in the first 3 innings of the series as we have seen above. England’s batters have managed 3.7 runs per false shot, while their bowlers have conceded 3.9 runs per false shot. If we look at the figures by bowler, then Moeen has conceded 6.2 runs per false shot. Anderson 3.3, Robinson 3.2 and Broad 3.0. Josh Tongue has been an improvement on Moeen, conceding 3.5 runs per false shot. By contrast, the extremely attacking Mitchell Starc induced 39 false shots in this 17 overs in the first innings. He conceded 88 runs, and also got 3 wickets - 2.3 runs per false shot.

As I write this before the start of Day 4 of the Lord’s Test, England could still win this match. Australia are 130/2 in the third innings and lead by 221 over all. Should Australia be bowled out in the next 100 runs or so, and should the weather be set fair, then, with Nathan Lyon missing, England could yet chase down the 300-350 they’re likely to require. It’s unlikely that the Lord’s pitch will break-up in the fourth innings. Pitches in England have not tended to deteriorate in this way recently.

So far, England’s problem lies with their bowling in these Ashes. Not with Bazball. Bazball is about taking chances. And England’s XI is well built to play that way. Whether it is well built to take 20 Australian wickets, is the big question. So far, in the first three innings of the Ashes, the answer is closer to No than it is to Yes.

It would help to define what a false shot is for a new audience and present the numbers in a table rather than a paragraph for ease of reading