India In The Field

In four Tests in England, India have been poor in the field for about an hour. That hour with the new ball arguably put them out of contention at Headingley. The bowling was wayward and seemingly aimless. They were trying to get wickets every which way, not doing well enough in any of them, and conceding a lot of runs in the bargain.

The reason there are few players averaging 50 in Test cricket today is that there are more teams on the Test circuit than ever who are rarely poor in the field. What does it take to avoid being poor in the field?

First, you need to have a good bowler bowling. Second, there needs to be a plan. This means knowing where the bowler is trying to get the dismissal, where he expects to concede runs. Plans can be very attacking - designed to chase wickets extremely aggressively, risking quicker scoring by the batting side. They can also be restrictive. When there’s help in the pitch, plans tend to be more attacking. When there isn’t, they tend to be attritional.

How much control a team exerts in the field depends on how many bowlers it has who are capable for enforcing the widest variety of necessary plans well. Currently, India rarely bowl a bad over the field. That’s why they can compete everywhere.

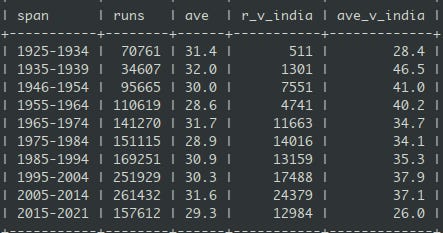

Since India played her first Test match in 1932, batting against India has always been an easier assignment than batting against the average Test team. The current era is the first time when this has not been not true.

This is even more acutely true outside Asia

This is not because of any psychobabble. Its because of the skill of the bowlers. When India are in the field, its always immediately obvious what they’re trying to achieve when each bowler is bowling. The Indian captain no longer just hopes that the bowler will bowl to the plan, he expects it.

Ravindra Jadeja is a truly great spin bowler as he has demonstrated in these four Tests in England. In recent years, England has been inhospitable for finger spin. Finger spinners have taken 3 ten wicket hauls in Tests in England since Muralitharan did it twice in 2006. No visiting finger spinner has done it. Ravindra Jadeja has delivered 123 overs and conceded 2.2 runs per over in this series. England’s finger spinners have delivered 104 overs and conceded 3.3 runs per over.

Consider the consequences of this, since both teams have played 4 fast bowlers in every game. England’s fast bowlers have had to bowl 581 overs in the 4 Tests, to 517 by India’s. If Root were to use Moeen Ali or himself as much as Kohli has been able to use Jadeja, it would have cost him 135 extra runs compared to what Jadeja conceded for India. 135 runs in 4 Tests is an extra lower order batsman (or an extra out of form top order batsman).

It takes extraordinary skill to bowl to a field and control the runs as Jadeja does. And as good as Jadeja has been, he has not been at his absolute best. The new way of scrutinizing front foot no balls mean that he’s bowling no balls more often. He has also tended to take an over or two to settle into his spell. But even so, Jadeja has been impossible to hit. He’s too quick through air to allow the batsman to step out against him. He’s too accurate for the sweep to be sustainable. And his control of length is too good to allow too many square cuts.

In the fourth innings at the Oval, India’s expertise in the field was on show. All the bowlers bowled to their field. They knew why the field was the way it was, what the expectations were. On Day 4, they had been more attacking with the new ball, and on a very flat pitch (on which India’s last 4 wickets added 150 after Kohli was dismissed), conceded 77 in 32 overs, and 8 boundaries. In the first session on Day 5, when the ball was older, they shifted to a restrictive method and conceded 3 boundaries the entire session. Every bowler on show in that session from the limited Shardul Thakur, to the extraordinary Jadeja and Bumrah, bowled to their field, which was set to allow the bowlers to attack the stumps.

In the first 60 overs of ENG’s innings, they were kept down to 136/2 even though the wicket offered the bowlers nothing.

From overs 61 to 68, Bumrah and Jadeja broke the game open by taking 2 wickets each. Those wickets were a symptom of India’s relentless excellence in the field.

On another day, they might not have bowled England out. Pope might have survive Bumrah’s spell, and Root might have avoided playing on. England might well have gone to Tea with seven wickets in hand, and they might have saved the Test match. On a good pitch, this would not have been a surprising outcome.

India’s achievement was to make it difficult for England. To be fair to England, both sides have been able to do this in the field in this series. When there’s some help for the seamers, England can bowl two sessions without offering a bad over. Anderson, Robinson, Woakes, Wood and Overton, are relentlessly excellent. When there’s less help for the seamers, England are less able to exert control. Moeen Ali does not have the top spinner’s control which Jadeja has. And none of England’s fast bowlers (except possibly Wood) have the extra pace required to make something of a flat pitch.

India’s results are a consequence of this excellence in the field.