India Were Lucky In Australia

They played about as well in Australia in 2020-21 as they did in England in 2018.

In the week and a bit since Rishabh Pant drove a wide full-toss to the long-off boundary to take India from 325/7 to 329/7 and seal a 2-1 series win for the visitors, we have had a wide array of commentary, from the regulars to the occasionals. Even the New York Times reported the series win.

Trillions of electrons have been worked to exhaustion trying to explain this extraordinary result. There are, by now, a million reasons in the public record which explain why India were good enough to win, and why Australia were bad enough to lose. The Australian bowlers were tired. India were fearless. The Australians were predictable and familiar. India were varied and intrepid, while Australia were unimaginative and stale. India did this good thing, and Australia did that bad thing. The winners must be virtuous, and the losers must be defective.

Writing to the result is an essential feature of psychobabble. After all, if the cricketers’ actions - their labour - are merely symptomatic of larger pathologies (fearlessness, staleness, which can only be observed from above, then the actions are not worthy of scrutiny at all. Only outcomes matter. This is partly because actions are harder to observe well when compared to outcomes (which are available in the scorecard).

For more than a decade, ESPNCricinfo have maintained an elegant measure of actions. They call it Control. Control asks of each delivery - “was the batsman in control?”. So, for example, if there’s a leading edge or an outside edge, or an inside edge, the batsman is not in control. If the batsman plays and misses, the batsman is not in control. If the batsman get hit on the pads, the batsman is not in the control. If the batsman gets out, then barring a run out, the batsman is not in control. This measure evaluates the batsman’s action. By inference, it also measures the bowler’s capacity to create uncertainty (the frequency of not in control deliveries, or false shots). This is, as far as I know, the only systematic quasi-public record of this type in cricket. Siddarth Monga has reviewed the control numbers for this series in some detail here. He provides some insight into individual match ups.

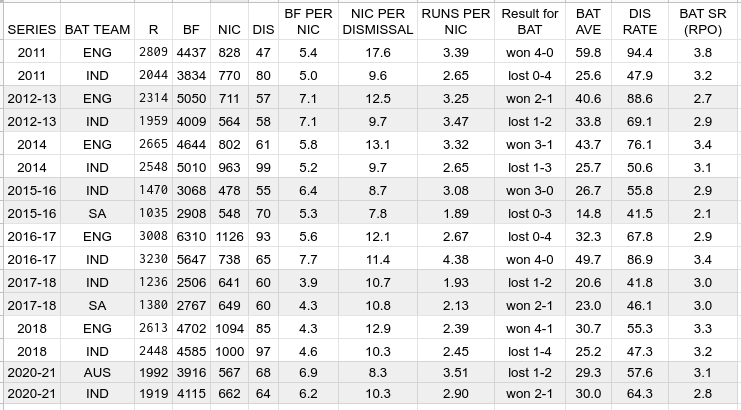

What does this record say about the four Tests in Australia? Over the course of the series, Australian batsmen were not in control once every 6.9 balls. Indian batsmen were not in control once every 6.2 balls. Further, Australian batsmen were dismissed once every 8.3 times they were not in control, while Indian batsmen dismissed once every 10.3 times they were not in control. So in the headline, the Australian batsmen batted with greater assurance than the Indian batsmen, but Indian batsmen happened to survive more deliveries out of control than the Australians. All told, the Australian bowlers created not in control responses from Indian batsmen 662 times for 64 wickets. The Indian bowlers created not in control responses from Australian batsmen 567 times for 68 wickets.

India had a favorable beginning at Adelaide. In the first innings, they survived 92 deliveries out of control to get to 244 all out, and then India’s bowlers earned a 53 run lead by taking 10 Australian wickets forcing 75 deliveries out of control. In the third innings India collapsed to 36 all out, losing 10 wickets in only 33 not in control deliveries. Overall, Australia had the rub of the green at Adelaide.

At Melbourne Indian bowlers took 20 Australian wickets in just 136 not in control deliveries. Australia had to bowl 109 just to get the first 10 Indian wickets. In part this is because, having being bowled out for 195, Australia had to defend runs relatively early when India batted and couldn’t place as many fielders in catching positions as they would like.

At Sydney, Australia were bowled out twice over 163 not in control deliveries by their batsmen. India had the rub of the green over the first innings. In the 4th innings they had an unusual amount of good fortune. Australia created 135 false shots (not in controls are essentially false shots) for only five Indian wickets. Contrast this with India requiring 136 to get 20 Australian wickets at Melbourne.

At Brisbane, just as at Sydney, India were relatively lucky with the ball when Australia batted first. They didn’t create a lot of false shots - about 1 every 8 balls in both cases. Both they got a wicket once every 8 false shots too. India’s 10 first innings wickets fell over 97 false shots. In the 3 innings, Australia chased quick runs and got them. They scored at 3.9 runs per over (as opposed to 3.2 and 3.0 in the first two of the match, and the 3.4 India managed in the 4th innings. India created a false shot every 5.1 balls (roughly, once every over). In the 4th innings, Australia were not able to match this. They managed to create a false shot every 7.3 balls, and got a dismissal every 11.4 false shots.

While India had the rub of the green, especially in the last three Tests, a couple of other points are significant. First, Ben Jones of CricViz points out that India attacked the stumps 42% of the time compared to 39% by Australia. This is a relatively small difference. Over 100 overs, that’s 18 extra balls on the stumps from India compared to Australia. Part of this has to do with the fact that India played with Jadeja and Ashwin in 2 of the 4 Tests. Part of it has to do with India’s defensive leg-trap which was designed to kill the runs (or “bowl dry” as the Indian players describe it). Second, Mitchell Starc was suffering on the 5th day at Brisbane. This contributed to the relatively low false shot rate of 7.3. Third, Pat Cummins created a false shot once every 5 balls against right handers, and once every 5.7 balls against left handers. Josh Hazlewood was similarly less effective against left handers.

The bottom line then, is that India were luckier than Australia on the field. But this, by itself is not enough. The bigger point, which is evident from India’s Test performances especially since the start of 2018, is that India have a complete squad which enables them to compete on equal terms with any opposition anywhere in the world, including against Australia in Australia. So if India do enjoy a little bit of extra luck, this is now enough to put them over the top.

To see this difference, see the following comparison of India’s 3 tours to England in the 2010s. They lost all three times - 4-0 in 2011, 3-1 in 2014 and 4-1 in 2018. I’ve written a few essays about a few of the series listed below [1, 2, 3] which consider control data. The 2018 Indian tour was significantly different from the 2011 and 2014 tours.

In 2011, the English bowlers create forced false shots more frequently from the Indian batsmen than the Indian bowlers did against England. The story of that series was that England would bow well, dismiss India, and then Indian couldn’t bowl as well, allowing England to get into position which forced India to defend runs. At that point, England’s batting depth enabled them to build huge leads. England scored quickly because the Indian bowlers couldn’t bowl accurately enough to keep the runs down. In 2014, it was a similar story. Of the 9 first innings in the 2011 and 2014 tours, England batted first 4 times, and were bowled out once - at Trent Bridge in 2011. India took a first innings lead of 67 there, and then conceded 544 all out in the third innings. The other 3 times, England declared on 474, 591 and 569. India batted first 5 times and were bowled out under 224 on four of these occasions (consequently, when they bowled, they had to defend runs early and found it difficult to force dismissals). They got to 295 all out (recovering from 145/7) at Lord’s in 2014 and won. India played marginally better in 2014 than in 2011, but they just couldn’t match England’s accuracy and depth with the ball.

In 2018, it was a different story. India’s bowlers created false shots more frequently than England’s bowlers. But English batsmen enjoyed better luck than India’s batsmen overall (12.9 false shots per dismissal for England’s batsmen, compared to 10.3 for India’s batsmen). Part of this was because India had a longer tail than England - England have more players in their XI who could contribute with bat and bowl in English conditions. India basically ran out of batsmen in their XI before England did. The Indian tail in Australia was just as long as it was in England. But India’s bowlers enjoyed greater luck in Australia than they did in England. They produced more edges and fewer plays-and-misses.

In England in 2018, India were a few inches away from win the series 3-1. In Australia in 2020-21, India were were a few inches away from winning 3-0 or losing 3-0. This is the nature of Test cricket between evenly matched sides on result pitches.

India’s great achievement under Ravi Shastri, Anil Kumble and Virat Kohli is that they’ve built a squad which has the quality and the depth in batting, fast bowling, spin bowling and wicket-keeping to compete in any conditions against anybody - whether it is England in England, or Australia in Australia. Occasionally, they’re going to get lucky and win series. At other times, they may be less lucky and lose series. But unlike Indian squads in earlier eras, they are sufficiently complete now to always be competitive.

Individual series results are a symptom of the relative quality of squads. Quality is like the climate. It is not like the weather. India have a high quality squad in both breadth and depth.

Australia did not play poorly in this series. Its just that they faced an Indian squad in this series (as they did in 2018-19) which is significantly superior, and more complete when compared to previous Indian touring squads to Australia. Before 2018-19, Indian touring squads to Australia never had the bowling to compete there. So the best India could hope for was enough flat pitches to avoid a mauling. And when those flat pitches were not forthcoming, a mauling was the result.

The way to think about this is that when the current Indian squad plays, the average quality they can offer to contest each ball in overseas conditions is higher than it has been with Indian teams of the past.