Sourav Ganguly played 113 Tests and 308 ODIs for India. He’s arguably the best left-handed batsman to play for India, especially in Test cricket. He captained India in 49 Tests and 146 ODIs. Only MS Dhoni and Virat Kohli have captained India in more Tests, and only Dhoni and Mohammad Azharuddin did it in more ODIs. In terms of caps and captaincy, Sourav Ganguly has a claim to a seat at the top table of India’s cricket history.

However, this - cricket - is not what makes the headlines about him. The conventional wisdom about him says that he was a uniquely gifted leader who led the Indian team out of the doldrums. Ganguly himself gives leadership a prominent position in his book A Century Is Not Enough. One of the three sections in the book is titled “Becoming a Leader”. Stories about his ‘leadership mantra’ abound. Krishnamachari Srikkanth compared Ganguly to Clive Lloyd. Sanjay Manjrekar observed that Ganguly gave India belief. There are business school case studies about Ganguly’s leadership (not free to read, and I haven’t read this one. The table of contents tells a conventional story). Ganguly points to his ability to identify talent as his biggest legacy. The leadership thing has become a cultural artifact to the extent that corporate executives speak of liking Ganguly’s “leadership style”.

Leadership, according to Ganguly and the many who speak for him, appears to consist of instilling belief, and identifying and backing talent. Did Ganguly do these things uniquely well? If the answer is yes, then the claims about his leadership have merit, and may be more than just a run-of-the-mill personality cult. Given that this is cricket, the answer will be found in the cricketing record. Let’s take a look.

Of the achievements listed under Ganguly, the first one which comes up most often is the fact that India won Test matches overseas for the first time since 1986. This is true. In 27 Away Tests under Azharuddin, India won 1, lost 10 and drew 16. In 13 under Tendulkar, there were 6 defeats and 7 draws. Outside Asia, there were 3 wins and 7 defeats in 17 Tests under Ganguly, while there were 15 defeats and 0 wins in 32 Tests under Azharuddin and Tendulkar. For comparison, the figures for Kohli read 8 wins and 10 defeats in 22 Tests. If going from 0 to 3 wins is due to leadership, what is going from 3 to 8 wins due to?

It is worth asking this because even though India won at the Queens Park Oval in 2002, they lost in Bridgetown and Kingston. And this time it wasn’t to Ambrose, Bishop, Rose and Dillon, but to Adam Sanford, Cameron Cuffy, Pedro Collins and Mervyn Dillon. In cricket terms, there’s a strong case to be made for the proposition that the 1997 Indian touring party to West Indies did better than the 2002 India touring party, and that the 1997 West Indies squad was superior to the 2002 West Indies squad. The same can be said of the 1990 and 1996 England squads and the 2002 England squad. The same is obviously true of the 1992 and 1999 Australian squads and the 2003 Australians. India were better in Australia in 2003-04. But it is hard to argue that Anil Kumble's new googly was Ganguly’s doing. Or that Sehwag opening the batting was a stroke of tactical genius. It wasn’t. Sehwag opened the batting for the same reason that VVS Laxman opened the batting at the start of his career - because a spot was not available in the middle-order and Sehwag, like VVS Laxman, was obviously too good for the Ranji Trophy game and belonged in the Test team.

Consider where the Bridgetown Test might have gone had Ian Bishop had injured himself and been unavailable to bowl for most of the 4th innings, and forced Carl Hooper to bowl from one end, in the same way that Jason Gillespie was unavailable for most of India’s 4th innings at Adelaide, forcing Steve Waugh and Simon Katich to fill in on a wearing wicket. Or consider where the Johannesburg Test of 1997 might have been had it not been for the weather.

The fact remains though, the India did win 3 Tests overseas under Ganguly after coming close at least as many times in the previous decade (Adelaide 1992 is the third case). Its is harder to credit the view that Ganguly provided his contemporaries - Kumble, Tendulkar, Dravid, Srinath and Laxman - with some additional steel and made them better competitors. It is even harder to credit the proposition that Ganguly was uniquely and solely responsible for identifying talent and backing it. It is hard to miss ability as blindingly obvious as Virender Sehwag or the 18 year old Harbhajan Singh. There’s a whole BCCI system, and hundreds of coaches, former-players, umpires and trainers who have the eye to spot exceptional talent. They form a deep, mature scouting network which forms the basis of India’s bench. This has been the case for decades.

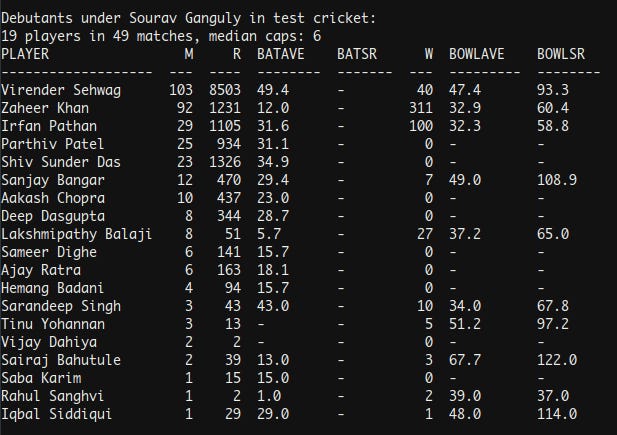

Consider the evidence. 19 players made their Test debut under Sourav Ganguly. Two - Virender Sehwag and Zaheer Khan - went on to win more than 30 caps for India. The median debutant under Ganguly won 6 caps.

In contrast, 26 players made their Test debuts in 47 Tests under Azharuddin. Of these, four - Dravid, Kumble, Ganguly and Harbhajan Singh - played more than 100 Tests. Javagal Srinath played 67 Tests, Nayan Mongia 44 and Venkatesh Prasad 33. The median debutant under Azharuddin won 16 Test caps. If Ganguly’s record of identifying talented players is supposedly makes him uniquely good at this, what can we say about Azharuddin’s record?

Consider Mahendra Singh Dhoni’’s record. Kohli (86), Pujara (77), Ashwin (71), Rahane (65), Vijay (61), Ravindra Jadeja (49), Shami (49), Saha (37), KL Rahul (36), Dhawan (34) are among 25 players who made their Test debuts in 60 Tests under Dhoni. The median debutant won 24 caps.

Consider Rahul Dravid’s record. 11 players made their Test debut in 25 Tests under Dravid. The median number of caps is 26. Ishant Sharma, MS Dhoni, Gautam Gambhir and Yuvraj Singh all made their debuts under Dravid.

There were 14 debutants under Sachin Tendulkar who evidently couldn’t do anything right as captain and put himself under so much pressure that it began to affect his batting. One of these 14 was VVS Laxman. The median number of Test caps for a debutant under Tendulkar was 4.

Looking either side of Ganguly’s tenure, it looks like every captain other than Tendulkar identified more players who won more Test caps than Ganguly did. But it is never claimed that these captains were exceptionally good at identifying and backing talent. Despite what is reported in the press and what obviously disinterested players say in press conferences and media interviews, the ability to identify top quality talent is fairly widespread among players and coaches who play and train first class teams and age-group teams. Perhaps it is because there is an infrastructure in place which allows players to demonstrate their gifts.

That debutants under Ganguly didn’t get as many chances as debutants under Dravid or Dhoni or Kohli or Azharuddin did is unlikely to be because of any vendetta anybody held against these players. It’s far more likely to just be the natural variation one would expect in patterns of selection which depend on things like the number and type of available spots in the squad. There’s nothing in the record to suggest that Ganguly was uniquely good or bad at identifying good players or nurturing them.

The corresponding ODI record is much harder to evaluate since India have often rested players for some ODI tours and in recent years, have even sent what might be considered second string ODI squads for some tournaments. This is not the case with Test squads. For example, 31 players made their debuts under MS Dhoni with the median number of caps being 12, while 30 players made their debuts in 146 ODIs under Ganguly, with the median number of caps being 30 (Lakshmipathy Balaji). In contrast, only 9 players made their debuts in 79 ODIs under Rahul Dravid. The median number of caps for debutants under Dravid was 53 (S Sreesanth). There have been 16 debutants in 89 ODIs under Kohli, with the median debutant winning only 6 caps. 174 matches under Azharuddin saw 34 debuts and the median number of ODI caps earned was 17.

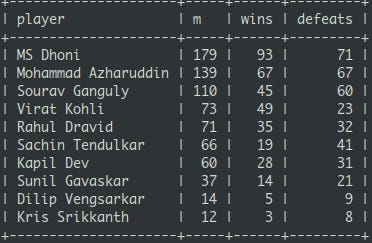

When it comes to ODI results, India under Ganguly were worse than under anybody since 1980 except Tendulkar. The Ganguly era was marked by India playing and hammering minnow teams (for now, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh or one of the Associate members) while losing as a rule to the 7 more established Test playing teams. A more rigorous definition of a minnow is used in the charts below. It uses an ELO based rating (described here) and all teams with an ELO rating under 0.45 at the start of a match are classed as minnows.

The table below gives India’s ODI record by captain against non-minnows (i.e. against good quality opposition).

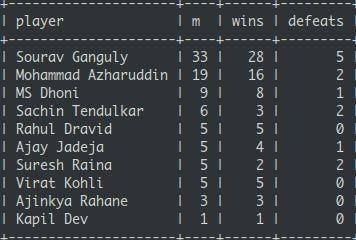

The table below gives India’s ODI record against minnows (teams with an ELO rating under 0.45 at the start of the match, or Associate Member teams).

The record shows why the public perception about the Ganguly era being successful is so widespread. India played an unusually large number of games against minnow teams (33 out of 143, plus 3 abandonments) under Ganguly compared to other periods. The record shows not only how much better the Indian teams under Kohli and Dhoni have been compared to their predecessors, but also how much better the Azharuddin and Dravid eras were compared to the Ganguly era.

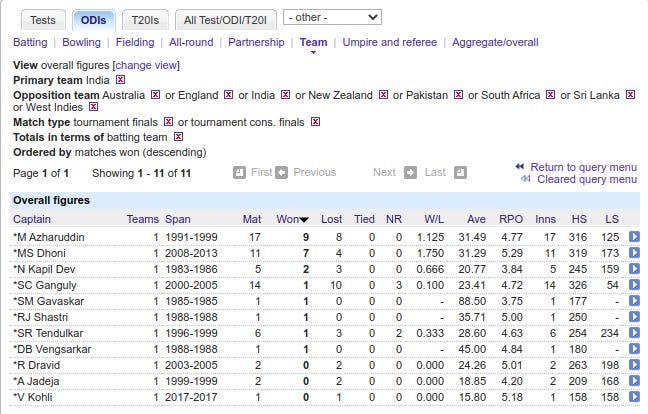

There is (unsurprisingly, if you accept that the record represents the quality of a team) a damning corollary to this poor form in ODI cricket. This has to do with finals. The Ganguly era is remembered mostly for a famous final at Lord’s in 2002. India beat England and Ganguly celebrated by taking off his shirt at Lord’s. To see just how significant this episode was to him, consider that it forms the title of a chapter in A Century Is Not Enough.

India reached 14 ODI finals (a screenshot is given below) against non-minnows under Sourav Ganguly’s captaincy, lost 10 and won 1. They did better under every other captain. Apart from anything else, this brings the whole “mental toughness” stuff into question. Under Ganguly India lost the ICC Champions Trophy Final to New Zealand on October 15, 2000, the Coca-Cola Champions Trophy Final to Sri Lanka on October 29, 2000, the Coca-Cola Cup final to West Indies on July 7, 2001, the Coca-Cola Cup final to Sri Lanka on August 5, 2001, the Standard Bank Triangular final to South Africa on October 26, 2001, the 2003 World Cup Final to Australia on March 23, 2003, the first VB Series Final to Australia on February 6, 2004, the second VB Series Final to Australia on February 8, 2004, the Asia Cup Final to Sri Lanka on August 1, 2004, and the Videocon Triangular Series Final to New Zealand on September 6, 2005. But they did beat England at Lord’s on July 13, 2002.

If nothing else, it remains a remarkable feat of marketing and public relations to take that record in finals and hide it behind a fabled day at Lord’s to weave a story about leadership and fearlessness.

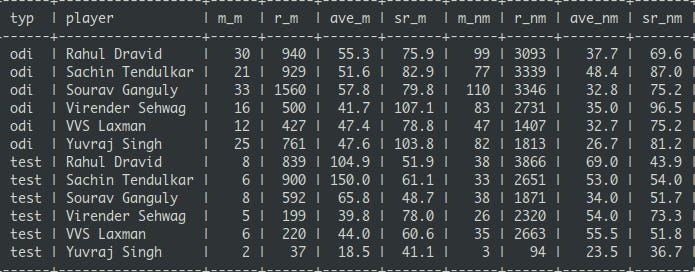

The chart below gives the batting record of six Indian batsmen in matches under Sourav Ganguly’s captaincy. Fields ending with “_m” signify a record against minnows (as defined above), while fields ending with “_nm” signify a record against non-minnows. m, r, ave and sr signify matches, runs, batting average and scoring rate (per 100 balls faced) as usual. Ganguly averaged 32.8 and scored at 75.2 runs per 100 balls faced against non-minnows in 110 ODIs as captain. For a specialist batsman in a batting friendly era, that’s a record which would have the selectors of any team with aspirations to being one of the top 4 or 5 in the world looking for a replacement. A Test batting average of 34 in 38 Tests as a specialist batsman would invite similar scrutiny from the selectors.

That Ganguly did not attract this kind of entirely reasonable scrutiny until Greg Chappell arrived, was because he was captain. He may never accept that it was entirely reasonable for Chappell to ask him to stand down from the eleven in late 2005, but this doesn’t change the evidence which was overwhelming. The evidence is strong enough to invite the Brearley Question. Mike Brearley is considered to be one of the finest Test captains of all time. Yet, Brearley averaged 22.88 playing as a specialist batsman for England in his 39 Tests. The obvious question for Brearley would be - if he was really such a great captain, why didn’t he do the obvious and drop himself and allow a better player who would contribute more runs to play in his place? Would that not have improved England’s prospects?

There is a second reason why Ganguly escaped this scrutiny. It runs in parallel with why the public perception is at odds with the fact that India under Ganguly were a losing ODI side. It is that he made a lot of runs against the minnows and those matches came often (one in every 4.3 matches was against a minnow opponent under Ganguly’s captaincy). Perhaps this is illustrated best by Ganguly’s record in the 2003 World Cup. Against Australia, England, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, New Zealand and Australia (in the final), Ganguly made 9, 19, 0, 48, 3 and 24. Against Netherlands, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Kenya, and Kenya (in the semi final), Ganguly made 8, 24, 112*, 107*, 111*. It made Ganguly the 2nd highest run getter of the tournament behind Tendulkar. Against non-minnows though, Ganguly made 103 runs averaging 17.2, scoring at 71.5 runs per 100 balls faced, compared to Tendulkar’s 300 runs averaging 50 and scoring at 91.7 runs per 100 balls faced.

Despite all this, when it was suggested by Greg Chappell that perhaps Ganguly should stand down for a while, this was considered to be an outrage. The Chappell-era story has been recounted by several players from that era, though significantly, Dravid, Dhoni and Kumble have not spoken or written about it yet. It is worth reading Ganguly’s view of that period from A Century Is Not Enough.

For now, it is worth asking whether claims made on behalf of Ganguly’s ability to lead and inspire are merited. What did Ganguly do that other captains from Azharuddin to Kohli (and perhaps even before Azharuddin) did not do just as well, if not better? The major effect of Ganguly’s captaincy seems to have been to destroy him as a batsman. This is a shame because he could have ended up with a Test career which would have put him in the same bracket as his three great contemporaries - Dravid, Jacques Kallis and Ricky Ponting. And imagine where India would have been if they’d had not one but two players as good as Dravid.

If you still hold that in cricket, there are intangibles which are self-evidently significant even though their effect does not appear anywhere in the record, then you are immune to empirical evidence. But if you believe, like I and almost every other cricket fan I know do, that cricket is a game of batting and bowling in which balls are bowled and faced, and runs are scored and wickets are taken, and players who are better at this than others are better players, and teams which are better at this than others are better teams, then, given the evidence, one cannot help but wonder about the basis of these claims about leadership and belief which are made on behalf of Sourav Ganguly.

Ganguly still had a fantastic international career. He’s not in the dock here. It is the imaginary Ganguly who has been made out to be a cricketing Napoleon who is.

'Ganguly still had a fantastic international career'

I wonder how that conclusion is reached. By most accounts, it seems he had a few good initial years as a batsman and one good year right at the end. Being mostly less than mediocre for more than half his career surely can't make a 'fantastic' career?

For an article that claims to be data-based, there is a lot of vindictive non-sense here.

For instance, the author writes, " Or that Sehwag opening the batting was a stroke of tactical genius. It wasn’t. Sehwag opened the batting for the same reason that VVS Laxman opened the batting at the start of his career - because a spot was not available in the middle-order and Sehwag, like VVS Laxman, was obviously too good for the Ranji Trophy game and belonged in the Test team."

--Ganguly wanted someone like Hayden in his team. That is why Sehwag was promoted to open. Funny thing is you say something which is diametrically opposite to the opinion of the person who is directly concerned i.e. Sehwag.

"Its is harder to credit the view that Ganguly provided his contemporaries - Kumble, Tendulkar, Dravid, Srinath and Laxman - with some additional steel and made them better competitors. "

---Why is it hard when they admit it themselves? Just because it doesn't prove your hypothesis?

"If you still hold that in cricket, there are intangibles which are self-evidently significant even though their effect does not appear anywhere in the record, then you are immune to empirical evidence. "

---What nonsense. You think non cognitive traits like growth mindset , grit, creativity are not predictors of success because they are not captured or measured? There is an entire field in educational psychology delving on these topics.

--The fact is his peers who played with him for a decade or so have attributed him with the qualities that we associate Ganguly with. I will take their word over yours any day.

--You are suffering from a clear case of confirmation bias.

Also a general caveat for the readers of this post, there have been a lot these so called "data journalists" (Harigovind Sankar being another one) who conceal their confirmation biases under the garb of data and try to hoodwink readers into thinking they form cogent arguments. They are the modern day quacks and you will find them in every discipline.

Manipulating descriptive statistics to prove one's point has been going on for ages. Any article that mixes data with personal claims emphasising on a particular point of view where there is a lack of data set is a direct example of the author's motivations.

The biggest indicator of Ganguly's achievements is the extremely high regard he is held at by fellow cricketers. It is of much more value than these half baked so called "data driven articles".

Now, if you believe that even Ganguly's toughest opponents half fallen prey to the PR machinery surrounding him, then with equal vehemence I will claim this article has been written by a quack wanting his share in the limelight.