The news that James Anderson and Stuart Broad had been dropped from England’s Test team produced a great deal of comment among cricket fans and journalists. It is not every day that 1177 Test wickets are dropped from a Test squad. England’s failure to force a result against West Indies in Antigua has renewed questions about this selection decision.

And yet, there is a reasonable cricketing case for this selection decision even without getting into the fact that Anderson is 39 and Broad is 35, making them the oldest new ball pair in Test cricket since Courtney Walsh (38) and Curtly Ambrose (37) in the year of their retirement. The reason could be termed the Broad-Anderson paradox, and this is explained below. It is a question of balance in a bowler’s era.

The problem with conceding runs in Test cricket is twofold. First, as the runs conceded increase, the difficulty of scoring enough runs to match the opponent’s score increases. Second, as the runs conceded increase, the amount of time available to score enough runs to match the opponent’s score increases. Beyond a certain threshold, there isn’t enough time remaining in a Test match for the batting to score enough runs to overhaul the opponent’s match haul.

The 500th Test match was played in 1960. The 1500th in the year 2000. The 2450th Test match was recently completed in February 2022. The average number of six ball overs per Test in each of these spans stands at 355, 353 and 326. Considering only drawn Tests, it stands at 367, 371 and 360 respectively. Conservatively, one might estimate that to stand a chance of winning a Test match, a would have to get its 20 wickets in about 180 overs. At 3 runs an over, that means getting 20 wickets for about 540 runs, or 27 runs per wicket. If the record for each team in each Test is organized by the runs per wicket conceded as in Chart 1 above, then it is at the 29-31 runs per wicket mark that the win stops being the modal [the most frequent] outcome. Note that as bowling average rises, both defeats and draws become more likely, illustrating the two dimensional cost of the failure to take wickets - in terms of time and runs.

It is relatively rare in Test cricket for both teams to fail to take 20 wickets in Test. This has happened in 811 out of 2451 Tests (663/811 were draws). Both teams have taken 20 wickets in 314 Tests. The majority of Tests - 1327 - involve one or the two teams taking 20 wickets. In these 1327 Tests teams which lose 20 wickets and fail to take 20 opposition wickets have won 17 and lost 1196 times. Of those 17, 12 winning teams took 19 wickets (one opposition batter was either absent injured or the opposition declared 9 down in the 1st innings.) Of the remaining 5, four involve players either being absent due to injury or retiring hurt due to injury in both innings (Lawrence Rowe, Bert Oldfield, Les Ames and Bill Bowes, Gilbert Jessop), and the fifth was a Test in which Sri Lanka made 547/8d in their first innings and went on to lose by 14 runs. Inability to take wickets prompts contrivances like challenging declarations to force results. Those are rare and usually don’t work. In March 1968, Gary Sobers famously declared twice (526/7d & 92/2d) to try and break a deadlocked series and lost. He was hanged and burned in effigy in Port of Spain that night.

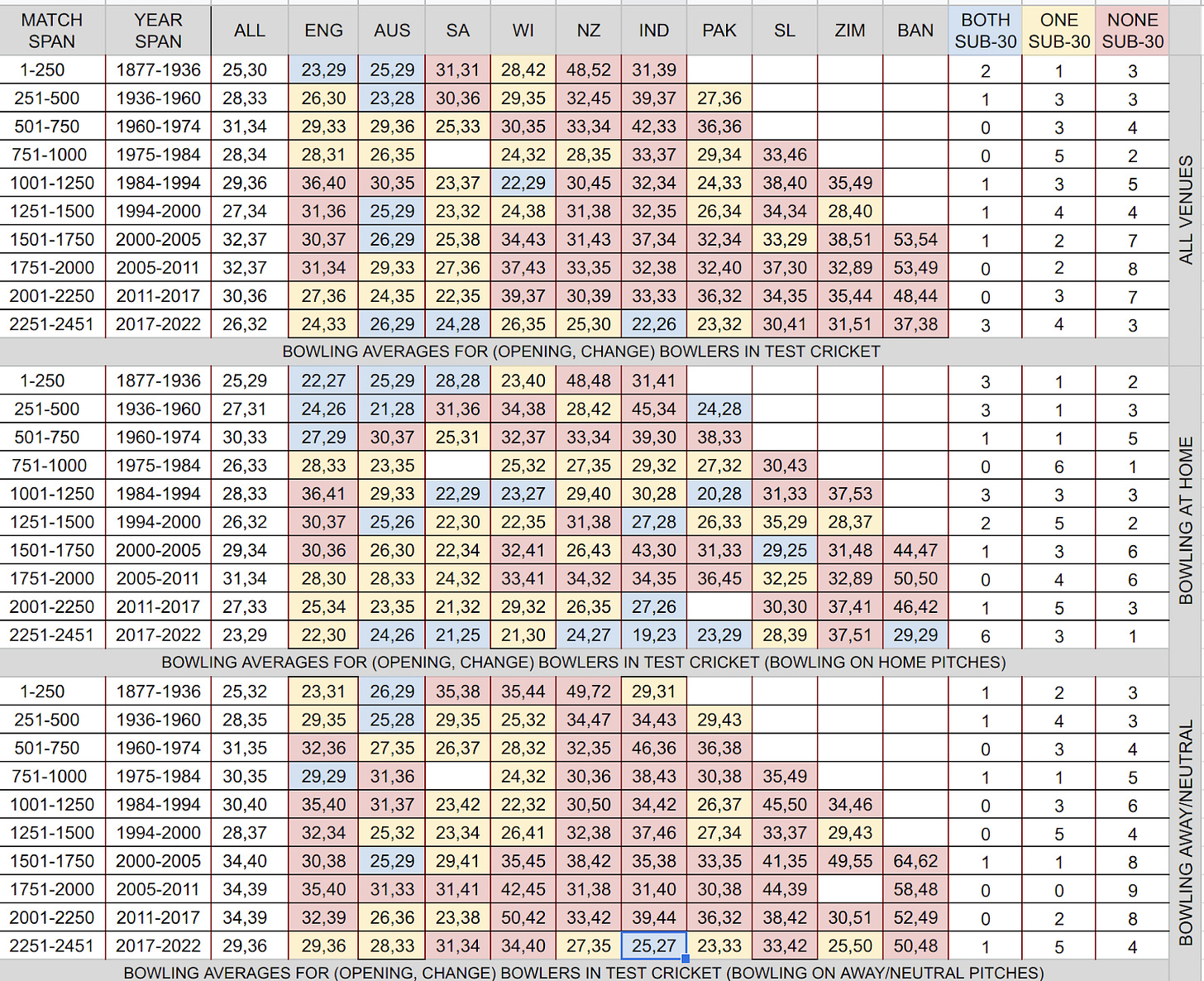

The Test record shows that taking 20 wickets is more or less essential for winning any Test. It also shows that to make a win the most likely result, conceding less than 30 runs per wicket is generally necessary because of the constraints of both time and average difficulty of scoring runs. Chart 2 organizes the history of Test cricket in terms of a team’s bowling average over consecutive, chronological, non-overlapping 250 Test spans. The bowling record is given in terms of the bowling average of the Opening bowlers, and the bowling average of the Change bowlers.

With the exception of India in the 20th century and West Indies until 1960, the Opening bowlers of all teams have bowled somewhere between 38 and 46% of their team’s overs (Table 1). Change bowlers deliver a majority of a Test team's overs as a rule, and their capacity to take wickets is consequently highly influential in determining how difficult it is to accumulate runs against a team.

The combination of figures in Chart 1 classifies bowling sides into three categories - teams in which both Opening and Change bowlers concede less than 30 runs per wicket, teams which one out of the two concede less than 30 runs per wicket, and teams in which neither concede less than 30 runs per wicket. This gives a picture of Test cricket in admittedly primary colors, but it helps to summarize the general propensity of teams to be able to challenge for victory (for which, as we have seen, 30 runs per wicket is a useful threshold) in a given period. The blue bowling attacks tend to take wickets quickly and cheaply enough to force a win regardless of whether the Opening bowlers or the Change bowlers are bowling. The yellow attacks tend to take wickets quickly and cheaply enough to force a win with either their Opening bowlers or their Change bowlers. The red attacks tend to take too long to take wickets to force wins as a rule.

The current era is an era of bowling attacks of great depth and quality (see Chart 1). My view is that most of this effect can be accounted for by the influence of DRS and improved drainage facilities around the world which mean that play is possible in weather conditions which would have seen days washed out in the previous century. The effect of this is seen in the improved capacity of teams to force results.

One consequence of a great bowling era is that the relative advantage of a top new ball attack diminishes. To focus on England generally, and Broad and Anderson specifically, in the 2011-17 period, England’s Opening and Change bowlers took their wickets at 27 and 36 apiece. This was better than 7 out of their 8 opponents in that period (leave aside Zimbabwe). In the 17-22 period, England’s bowlers struck at 24 and 33 apiece. But in this period, 6 out of their 8 opponents could match or better this rate. For Tests in England, the home bowlers (25/34) did better than every single opponent in the 2011-17 period. Australia (28/32), South Africa (29/37) and New Zealand (27/40) came close to competing in England. The four other opponents were comfortably worse bowling in England compared to the hosts in the 2011-17. In 2017-22, England conceded 22 and 30 runs per wicket for Opening and Change bowlers respectively. Australia (22/32), South Africa (24/33), New Zealand (20/27), India (30/28) and Pakistan (27/37), were all competitive in England compared to England. This means that even in England, Broad and Anderson’s new ball bowling has not given England the same edge in the 17-22 period as it did in the 11-17 years (see Note 3).

The same problem appears even more acutely away from home. Broad and Anderson’s wickets don’t go as far as they used to. What makes this problem more acute, is the fact that with age, the workloads and wicket outputs of England’s new ball greats are not improving. In fact, their wicket output has declined, both in terms of wickets per Test, and in terms of strike rate, especially away from home. This is noteworthy given that taking wickets has generally been easier in the 2017-22 period compared to the 2011-17 period (see Table 2).

This effect of facing strong attacks is seen in an interesting reversal in Tests outside England. Table 3 gives England’s batting and bowling averages in Tests in England and outside England. These are organized depending on whether or not England took 20 opposition wickets in the Test. Over the history of Test cricket teams which take 20 opposition wickets score 34.7 runs per wicket, while teams which fail to take 20 opposition wickets score 30.3 runs per wicket. This pattern holds for England in three out of four groups in Table 3. The one exception is for Away Tests in the 11-17 period. In that era, Tests in which England’s bowlers failed to take 20 wickets tended to be higher scoring games than Tests in which they succeeded. The record also shows that in the 17-22 period, England are doing nearly twice as badly in these Tests away from home, as they are in these Tests in England. In the 11-17 period they have done roughly equally badly (about 15 runs per wicket worse home and away in Tests where they fail to take 20 wickets). These figures indicate a problem of balance as much as a problem of quality.

To illustrate the problem of balance, consider Ravichandran Ashwin and Ravindra Jadeja’s records outside India in the 2017-22 period. Their contribution with the ball compares favorably to Broad and Anderson’s outside England. They also contribute more runs with the bat. You could argue that the Indian spinners are expected to be spearheads in away Tests in Asia, but not outside Asia, while Anderson and Broad are expected to be spearheads in away Tests outside Asia, but not in Asia. Opening bowlers manage 11.9 wickets per match in Asia, and 14.9 wickets per match outside Asia. Change bowlers manage 17.1 wickets per match in Asia, and 15.4 wickets per match outside Asia.

By playing both Broad and Anderson, England are forced to make compromises elsewhere in their eleven. It could be argued that in recent years, home batting line ups facing England have adopted a policy of seeing Broad and Anderson off (seen in their improved economy rate and declining strike rate) and waiting to milk the other bowlers who are picked as much for their batting as they are for their bowling. Since the emergence of Ollie Robinson, England’s first choice four pronged pace attack (a necessity against India and New Zealand in England, and against Australia in Australia), has been Anderson, Broad, Mark Wood and Robinson. It is striking that England have fielded this attack only once in the 9 Tests England have played from Robinson’s debut to the end of the Ashes (v New Zealand at Lord’s in Robinson’s debut Test). The compromise has always been to replace at least one of these four with a better batting bowler.

In England, the case for Broad and Anderson to play when they are available remains rock solid. But away from home, their output has been shrinking in an era in which the host attacks England face have improved significantly. England need to find a new balance for Tests outside England. Whether they succeed remains an open question. But it is certainly worth trying.

The Broad-Anderson paradox then, is as follows. In an era of great bowling attacks, the advantage provided by the individual great bowler declines. To keep up, these bowlers must either produce more wickets, or bowl more overs cheaply and give their captain control in the field. If they can't provide that, they must provide runs and bat higher up the order. If they don’t, they become a liability because accommodating them forces a side to compromise elsewhere, producing a poorly balanced eleven. This is true even if their bowling averages stand out compared to the other bowlers. Currently, Broad and Anderson don’t take enough wickets to justify batting at 10 and 11 and being considered spearheads. They don’t bowl enough overs to give Joe Root control in the field by closing one end down. They offer England a Change bowler’s wicket output and a tearaway’s bowling workload, and very few runs with the bat. When England face teams with deep attacks of their own, that leaves too much ground for the others to make up.

In their last 23 Tests together (in the years 1998, 1999 and 2000), Ambrose and Walsh averaged 9.5 wickets per match, bowled 50% of West Indies overs (a combined 82 overs per Test). In their last 25 Tests together for England (goes back to 2018), Broad and Anderson average 6.8 wickets per Test and bowl 42% of England’s overs (63 overs per Test). England could have used Walsh and Ambrose batting at 10 and 11, and delivering 20 extra overs per Test in this bowling era. It is hard to argue that they haven’t got a case to look beyond Broad and Anderson, especially on tours.

Notes:

1. Figures are current from Tests 1-2451 (March 15, 1877 - March 1, 2022)

2. This is generally true for smaller chronologies too. 250 match chronologies are given below.

3. These are figures for visiting teams to ENG, not the general Away figures for teams.