Dropping Players

I can think of no circumstances in which one could reasonably advocate that a player be dropped.

Players are dropped or replaced more often than people imagine. Since the start of 2018 - the beginning of a period in which India have played 42 Tests, including 28 away from home, 12 at home and one at a neutral venue - 19 different players have featured in India’s top 6 in Test cricket (ignoring nightwatchmen). 9 of these players have played at least 10 of the 42 Tests. Pujara (41), Rahane (39) and Kohli (36) have been mainstays. The personnel in the top 6 have changed 26 times those 42 Tests (the maximum number of changes possible is 41 in 42 Tests).

There is an evident order of preference for the middle order spots in the Test team. If all players are available, the three players preferred by India have been Cheteshwar Pujara, Virat Kohli and Ajinkya Rahane. This order of preference may change in 2022, with the number three and number five spots taken away from Pujara and Rahane.

When do the selectors do this? They do it for two reasons. First, when the incumbent is considered no longer good enough (Sourav Ganguly in 2005 for eg., or Murali Vijay in 2018), and second, if there’s an outstanding candidate who has to be played (Tendulkar in 1989 for eg.) Ganguly was the last established player to be dropped from India’s middle order (he’s one of only 2 to be dropped from the middle order since 1996 when Sanjay Manjrekar and Vinod Kambli lost their spots. The other being Azharuddin in 2000). He missed a few Tests in 2006, and then returned for a couple of years until his retirement. Rahane and Pujara have both been dropped for one or two Tests in 2018 when they were available.

Since the start of 2020, Pujara has 926 runs at 25.7 in 20 Tests, Rahane 775 runs at 26.7 in 18 Tests, and Kohli has 760 in 28.1 in 15 Tests. The three have managed 1 century and 17 half centuries in two years. They have reached thirty five 32 times in 94 innings between them, but reached 90 only twice.

In the two years before that (2018 and 2019), they averaged at least 40 each. They reached thirty five 46 times in 99 innings and managed 13 centuries.

If we compare the returns of the middle order from 2018 and 2019 to their returns in 2020 and 2021, the latter are measurably worse. By all conventional measures, this ought to put the places of all three bats at risk. The order in which places are in question, from the most precarious to the least precarious, are Rahane, Pujara and Kohli.

And yet, in the 2018 and 2019, India won 8 out of 8 home Tests losing none, and 6 out of 14 Away Tests, losing 7. In 2020 and 2021, thy won 5 out of 11 Away Tests losing 4, won 4 out of 6 home Tests losing 1, and lost 1 neutral Test (the WTC Final), despite the fact that all of the Away assignments in 2020 or 2021 were in New Zealand, Australia, England and South Africa, and the home assignments were against England and New Zealand, compared to the opponents in 2018 and 19 (West Indies home and way; Afghanistan and Bangladesh at home were some of them).

Run scoring has been more difficult in the assignments of 2020 and 2021, than it was in 2018 and 2019.

But all this is besides the point. It is unlikely to persuade those who are convinced that there needs to be a change, because there are questions of fairness and other less noble emotions (resentment, envy, the idea that ‘undeserving’ players continues to play) at work.

Matters have gotten to the point where the old line - that the selectors and team management of the best team in the world are incompetent - which usually lies submerged when India are winning (it has not had many opportunities to come up for air recently), is menacing the shore again.

This is a potent mix. A supporter base humiliated by a recent defeat, looking for a victim, and two players who are evidently short of runs but are apparently kept in play by stupid selectors… You know the drill. It is an old story.

Where is the cricket in any of this?

The logic of selection is simple. If there is a better player, then the better player has to be selected. Sachin Tendulkar was taken to Pakistan in 1989, not because there was an opening in the middle order, but because he was so palpably obviously outstanding. In the event, he played in place of Dilip Vengsarkar, who, from 1986 to 1988 was the world’s number one batsman, and 33 years old in 1989.

If there was a better player available, then regardless of what Pujara or Rahane were achieving, that better player would have played. If a better player is not available, then replacing one or both may give emotional satisfaction, but it is unlikely to improve the side (the desire to improve the side is, one presumes, the point of calling for their heads).

But here, we run into another problem. How does one tell whether a player is good enough to play Test cricket? Isn’t it all just mystical eyeballing by the stupid selectors?

There are patterns in the record. Look at the first class records of every player who has had a long Test career as a batsman, you find that all of them averaged 60 or thereabouts. The exceptional Tendulkar averaged 84.

This is not surprising. The evidence of 2000 odd runs is stronger than the evidence of three good months, or 30 minutes in the nets. Even Virender Sehwag, in 2001 (at the time of his Test debut), had 2744 first class runs at 58 to his name. First class records are a remarkably reliable indicator (with the solitary exception of Sourav Ganguly) of the probable quality of a player.

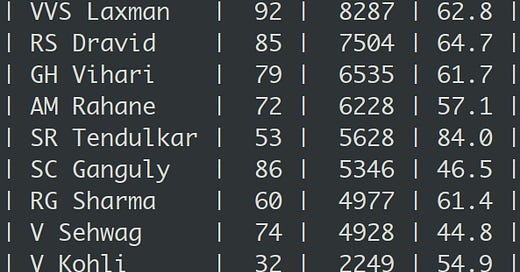

So, who are the contemporary players who fit this bill? The table below gives the first class records of all India eligible players who have averaged at least 50 in the first class game since 2014.

Unsurprisingly, all the probable candidates - Vihari, Gill, Rahul, Pujara and Iyer - have all been household names in recent years. They’ve all played for India. Priyank Panchal is an opener who regularly plays for India A. Barring Shubman Gill, none of them provide any evidence that they will do better than Rahane or Pujara.

Selection for India is shockingly systematic and normal. The selectors and the management running the best team in the world know what they’re doing.

There is another possibility. Could Pujara, Rahane and Kohli be in decline? This is always possible. All players go through a couple of bad years. And 33 is about the age when this tends to happen. Add the strangeness of the world of coronavirus bubbles to the mix and we’re in uncertain, uncharted territory. Could they be in decline? Yes.

Typically, bad form or decline is easy to isolate. If the wickets are good and the bowling is not particularly threatening, and everybody else is making runs, then the player(s) who are not making runs can be reliably said to be out of form. But this has not been the case with India in 2020 and 2021. Even the series which could be considered to be easy pickings for the players - home series against England and New Zealand - turned out to be played on result pitches (to put it mildly) featuring 3 day Tests which India won.

Could Rahane, Pujara and Kohli be in decline? Yes. Could the selectors decide that Rahane, or Rahane and Pujara, need a break and need to be taken out of the side and replaced with any of the other candidates (of which there are plenty - Shubman Gill and Rohit Sharma should both play if they are available, leaving a spot for only one out of Rahane or Pujara). The full strength line up (assuming 5 bowlers play) currently would probably read: KL Rahul, RG Sharma, S Gill, V Kohli, BAT, RR Pant, RA Jadeja. It is very likely that the open spot will go to someone other than Rahane and Pujara.

But does that mean that there is clear case for dropping them? No there isn’t. There isn’t a candidate who is better, going by the record. There isn’t clear evidence that these players are in decline. It is not the case that they’ve been failing uniquely in a period where lots of others have made big runs (Kohli’s record is probably the best evidence for this). And its not the case that there is any outstanding candidate who promises to be one level above any of them in the way Tendulkar was.

So here’s why there is never an occasion for an outside observer to advocate for a player to be dropped. If better options are available, those better options will have been selected already. If better options aren’t available, then there’s no clear case for dropping players. If a player is in decline, it will be noticed quickly. Readers will remember that when Sourav Ganguly was dropped in 2005 because he had averaged 34 against traditional top 8 opposition in the preceding 5 years in a batter era in which nearly every team had two or three bats averaging 50-55, the general reaction was not that Ganguly’s record meant that he deserved to be dropped. Rather, it was shock and outrage that he had been dropped. The public have an awful record when it comes to evaluating cricketers.

It follows from this, that for someone in my position (and yours) to demand that a player dropped, the motivation can only be unrelated to cricket. We can all have hunches that some player X is just waiting to become the next Lara or Tendulkar. But it is extremely unlikely that you or I can see that and the selectors and managers whose job it is to actually run the best team in the world don’t.

It is the normal practice at this point to just point out that “fans have a right to say what they like”. True. Just as others have an exactly equal right to listen to what fans say and show that they haven’t got the case they think they have. This is not a dispute about rights, but about merits.

In the case of selection, you and I haven’t got a case. Today it is Rahane and Pujara. Tomorrow it will be the player who replaces Rahane and Pujara today. Yesterday it was the player who Rahane and Pujara were primed to replace. It is unfair to all of them.

So logically, I can not think of a situation in which I could ever advocate that a player be dropped from the Test team. Its foolish to do so. The people whose job it is to do so have obviously superior evidence and know how. There is no cricket in advocating for a player to be dropped.

The Test team is not democratically elected. It is expertly assembled. That’s where the cricket comes in.

Hello. This is some great analysis, but from which database did you obtain the FC data tabulated in your piece? There is discrepancy between that and the FC data for the stated players on ESPN CricInfo. Is there a filter you applied to the same?

Ofcourse one can't drop a player better than VVS Laxman. But you can drop a player like H Vihari who hasn't disappointed yet.