My previous post on this subject produced comments which are the distilled essence of the arguments I’ve been hearing for years as I’ve posted what I found about the full record on various fora. Broadly, the responses fall in two categories. A first set of people say I’m motivated by some special hatred for Ganguly. A second set of people say that the record isn’t everything and that there are intangibles which I refuse to consider. In this essay, I’ll respond to both criticisms and also present some of the record which I didn’t include in the previous post.

The second criticism is dishonest and can thus can be dismissed out of hand. The people who lean on intangibles when the record contradicts what they hold to be the case claim that “not everything is evident in the record”. But what they’re really doing is merely shifting which record one should look at and which one we should ignore. In Ganguly’s case, the theory is that the work done in his era was directly responsible for future successes. This then, is not a claim about “intangibles”, but about deferred tangibles. But by calling them “intangibles” the deferment does not have to be justified. This is why the intangibles argument is dishonest.

I’m not inclined to dismiss out of hand the note that the first set of critics, who say I’m motivated by ‘hate’, seem to be attempting to sound. Suspicion is probably the correct term. But I’m not suspicious of Ganguly. The actual Sourav Ganguly has an actual international record which is available in full in the public domain - every single international match he played has been recorded fully. This is also the case with his contemporaries and almost all of his predecessors and successors. This makes it possible to summarize Ganguly’s record and that of every other player and compare them. This record is what it is. I’m suspicious of the claims made on behalf of Ganguly (which Ganguly has embraced from time to time), especially the “inspirational leadership” stuff. I’m suspicious of the imagined Ganguly.

Whenever things like “inspirational leadership” or “tactical genius” are touted as the central plank of a player’s sporting record, it should raise big, bold red flags. Professional sport is about specific technical skills being performed at an extremely high level. There is a direct correlation between those skills and measurable events on the field (in various sports: runs, wickets, maiden overs, completed passes, assists, goals, rushing yards, passing yards, sacks, interceptions, strike outs, hits, errors, winners, unforced errors etc.). And there is a further correlation between those measurable events and results.

There are players who are considered to be especially tactically astute. One common trope in cricket is that a particular player was “the best captain team X never had”. This was said of Shane Warne (and manifested itself, in some eyes, in his preference for Mark Taylor over Steve Waugh as captain). This should also raise red flags. When such flags are raised, one looks at the record. Warne’s international record is phenomenal. This lowers the flags - it suggests that in Warne’s case, the tactics talk is not deployed to cover-up for more basic shortcomings in performance. What you have in Warne’s case is an interesting disagreement about approaches. Both Taylor and Waugh were very successful batsmen and led successful Australian teams. Taylor went through a bad patch with the bad when he was captain and offered to stand down - a fact which reveals his attitude to representative sport and captaincy.

Ganguly’s record does not lower the red flags. In his case, when the record is examined, the stuff about “inspirational leadership” sounds like a filler for a record which is not there to be touted. Thus, every routine thing he did as captain got written about as though it was some heroic battle. Every Test captain ever has argued with the selectors about one player or the other, and every captain has got his way sometimes and not at others. Even Ganguly got his way with regard to Harbhajan Singh in 2001, but didn’t with regard to Dhoni for the Pakistan tour of 2003-04. India won both the Test and ODI series in Pakistan on that tour without Dhoni.

I subscribe to what might be called the Labour Theory Of Cricket. Under this theory, cricket matches are shaped primarily by batting and bowling. Whether or not a fast bowler’s arm is going over the perpendicular in the delivery action, causing the bowler to drift on to the batsman’s pads more frequently than he normally would, is of far greater significance in cricket than whether or not the captain screams at the players. Whether or not a batsman’s footwork is in tip-top shape, thereby ensuring that the batsman plays the ball as late as possible shapes more Test matches than any bowling change or tactical insight. Whether or not a spinner is rushing his run-up is of the first importance. It determines how well balanced the spinner is in delivery stride, and therefore, shapes how much control the spinner has. The Labour Theory Of Cricket presumes, rather quaintly, the cricket is about cricketing things. That it is not merely a stage for the latest fad in management-speak or psycho-babble. Under this theory, catches don’t win matches, but the frequency with which bowlers create chances does. This Theory requires that cricket be watched on its own terms, and not on terms governed by some pre-existing anxiety (Nationalism, Manhood, Managerial Fantasies or whatever else).

Under the Labour Theory Of Cricket, India under Ganguly were a losing team (as is evident from the record), because, in ODI cricket, they still played the ODI game which came into vogue in the early 1990s with its emphasis on top-order batting, and never quite did the work of developing the 4-8 positions the way that South Africa, Australia and Pakistan began to do in the late 1990s. There were really, only two major tactical disputes under the Ganguly era in ODI cricket. The first - who should open the batting, and the second, should Rahul Dravid keep wickets so that India can play a 7th batsman.

The first debate, predictably, became about how Ganguly “sacrificed” himself at the top of order to selflessly make way for Sehwag. This claim is easily examined. Under Ganguly’s captaincy, Ganguly opened 94 times (70 against non-minnows) for India, Tendulkar opened 83 times (61) for India and Sehwag opened 81 times (67) for India. Ganguly batted down the order 48 times (37), Sehwag 18 times (15) and Tendulkar 16 times (15). So, on the face of it, there’s some truth the proposition that Ganguly moved down the order to accomodate Sehwag. The record of the three players against non-minnows shows that it should never even have been a contest. Ganguly’s record is poor enough to sustain the view that had he not been captain, then Ganguly would have argued for dropping him (the way he argued for Dhoni to replace Parthiv Patel).

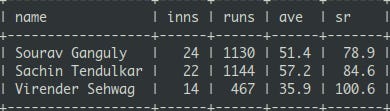

Ganguly, Tendulkar and Sehwag opening the batting in ODIs against non-minnows (defined using the ELO system as before)

Ganguly, Tendulkar and Sehwag opening the batting in ODIs against minnows (defined using the ELO system as before)

Ganguly, Sehwag and Tendulkar batting down the order against non-minnows under Ganguly’s captaincy.

Sehwag and Tendulkar were decisively superior as ODI batsmen when compared to Ganguly in the 2000-2005 period, and India produced more runs and better starts when Ganguly was not involved, than they did when he was. Against non-minnow opposition Sehwag and Tendulkar produced 1316 runs in 27 stands at an average of 48.7 and a scoring rate of 104.5 runs per 100 balls. Sehwag and Ganguly were less consistent (42.1/99.6), while Tendulkar and Ganguly were slower (48.4/82.5). The only available conclusion (confirmed by their individual records) is that compared to the other two, Ganguly was both slower and less consistent.

The greatest liability a team can have under the Labour Theory Of Cricket is to carry an player who is out of form or in decline in his primary skill. A batsman who is not scoring runs, or a bowler who is not taking wickets are liabilities which cannot be overcome by any amount of “inspiration”, speech making, impartation of self-belief or anything else. The standard of competition in professional cricket is just too high for this type of self-delusion to not hurt a team. It essentially amounts to the team playing 10 v 11 against top class opposition (such as the top 3-4 teams in the world consistently offer).

In Test Cricket it is a similar story. Here is an example of how Ganguly’s batting record during his captaincy stacks up within the landscape of Test cricket. The tables below show the 60 most prolific run scoring captains in Test cricket so far, from Graeme Smith, to Chris Gayle. Almost all of them (except Dhoni, Daniel Vettori, Brendon McCullum and Jason Holder) are specialist batsmen. The table gives two averages for each player. The first is the player’s batting average, while the second is the combined batting average for the other 10 players.

There are some extraordinary figures in these sixty names. Bradman, Steven Smith and Kumar Sangakkara stand out. Kohli, Sobers, Lara, Gooch and Jayawardene all average around the 60 mark.

58 out of 60 players in this list average better than the rest of the team. This, for a specialist batsman, is not unexpected. After all, on average 5 of the other 10 players are usually not in the XI as specialist batsmen - their primary role is bowling or keeping. The two exceptions are Sourav Ganguly and Michael Vaughan.

Michael Vaughan’s is an interesting case. His Test career lasted 10 years (1999-2008), during which he played 82 Tests. He had a phenomenal year in 2002, but after taking over the captaincy from Nasser Hussain, averaged only 36 in 51 Tests as captain, and only 33.7 in 47 Tests against traditional top 8 opposition. This record is not dissimilar to Ganguly’s. But unlike India, in England, there was s till some adherence to the Labour Theory Of Cricket and observers still scrutinized the captain’s batting and bowling. By 2008, Geoffrey Boycott’s criticisms came to head. When he discussed England captains, Boycott refrained from the patronizing “Prince of Calcutta” stuff, perhaps because he knew his audience in each case. The observation that Vaughan wasn’t playing well was well supported by the record, and as is the case normally in sport, Vaughan stood down.

When Greg Chappell reported to the Indian board that Ganguly wasn’t playing well enough to be captain, this was seen as a betrayal. Under the Labour Theory Of Cricket, Chappell’s observation would have been taken as nothing other than a perfectly reasonable observation given the cricketing evidence, and the Board and the Selectors would have done the needful (as they usually do - for example India don’t play Ashwin - their greatest contemporary wicket taker - as a regular in their ODI side). Instead, so strong was the Ganguly personality-cult by 2005, that Ganguly went to war with Chappell and found enough buyers in the media to, if not save his job, then at least to destroy Chappell’s.

My suspicions about the Ganguly-era, initiated by the inspirational-leadership-BS (essentially, it implied to me that there was no batting, bowling or results to speak of), turned out to have been well-founded when I looked at the record. It seemed to be something worth writing about. By the standards of some contemporary personality cults in other arenas of public life in different parts of the world, the Ganguly example is the Walt Disney version. This makes it a useful example as we try to navigate today’s world as voters, consumers, individuals and fans.

But there is a tragedy in the dark road Ganguly seems to have gone down in the period from 2000 to 2005. This period should have been his cricketing prime. Consider this. Ganguly’s Test record against non-minnows as captain reads 1871 runs at 34 in 38 Tests. This was in the unusually batting friendly era of 2000-05. His Test record against non-minnows when he wasn’t captain reads 4440 runs at 45.3 in 61 Tests. Ganguly spent the prime years of the international batsman (age 28-33) as captain seeing himself as an embattled underdog and destroying his own batting. What might have been, for both Ganguly and India, if his prime years had been spent, as most professional cricketers do, focusing on his cricket instead of being spent fighting imaginary enemies and sustaining massive PR campaigns alternating in hagiography and conspiracy theories?

It is difficult to reconcile the non-captain Ganguly - a superb batsman who, in his prime years should have advanced to the batting top table of his generation the way, for example, Hashim Amla did - with the paranoid mediocrity who comes across in A Century Is Not Enough. This is what makes the gap between Ganguly’s image and the record both disquieting and tragic.

For the test cricket average list, can we filter the list by no 6 test batsman? Ganguly played in a team at no 6 with two of the most decorated run getters of all time - Dravid and Sachin. At many batting friendly matches Ganguly would come to bat only to all few runs quickly before innings declarations after Sachin/Dravid have piled up runs. He wasn’t a great test batsman, but certainly not as bad as your stats portray him, there are nuances between the stats not easy to decipher.

In the ODIs, Ganguly was one of the greatest till he reached 9000 ODI runs, his form dipped after that. Took awful amount of innings to reach 10000. Sachin was out of the team for a long time. Sehwag would go out and play his short and fast innings irrespective of the game condition. Dravid was so poor and he had to be made wicketkeeper to be included in the team. Ganguly didn’t do well under pressure with falling fitness and the pressure from board’s internal politics. I mean which country has every presented a pitch which would favour the opposition instead of the home team? Instead of all this, he should have focused on his batting, his numbers would have ended better. Opening the batting always, take advantage of the field restrictions, and by the time spinners were called, he would have been set and a few sixes would have taken his score to 45+. Instead of that he focused of the team, backed a few players who would become champions in future, and kept on playing on big occasions (champions trophy or World Cup, somebody had to score those 100s against minnows). And thus players and people rate him a a great captain.

About the intangibles, Labour theory and team environment: the 2007 world cup team (although, admittedly it had Ganguly in it but not as captain) was probably far better than the 2003 team on paper (which is basically labour theory as I understand). However, the 2003 team performed far better. I would love to hear your opinion on that.

In my opinion performances in high stake games should get more weight in your analysis for obvious reasons (as they are remembered more and gets more global attention, so the mental aspect is very high). For example, the Champions trophy matches, games against Pakistan (which are definitely high stake for India), World cup matches, away tests etc should have more weight. One cannot compare a win in a dead rubber in a 5 match series with Sri Lanka on home turf with the same weight as compared to a win against Sri Lanka in a world cup super 6 match.

In any case, your analysis holds water no doubt about it. But I cannot agree completely with the Labour theory, and counting all matches with equal weight.