Since the 2019 World Cup final, England have won 29 and lost 35 One Day Internationals. Since the 2023 World Cup final, they have won 4 and lost 13. This puts England in 9th place in my ODI ELO ratings (described here), outside a hypothetical qualification cut-off for a Champions Trophy style short tournament featuring only the top eight ranked teams.

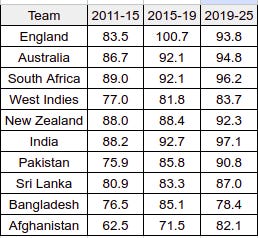

Why are England losing? Much of the discussion about this question focuses on what England have been doing. But perhaps the answer lies in what other teams have learnt to do in the last six years. The table below gives the scoring rates (per 100 balls faced) of the top seven batting positions in ODI cricket for the ten listed teams in matches involving only the 10 listed teams. The top seven batting positions face about 40 out of 50 overs on average.

In the 2015-19 period, the approach embraced by Eoin Morgan meant that England’s top seven were scoring, on average, 19.2 runs more than the next best team in the period (India) over 240 balls. Since then, England have found it difficult to sustain their scoring rate, while other teams have caught up with them. The competitive advantage provided by England’s approach in those early years has vanished.

Part of the reason for the small decline in England’s scoring is that other teams have also stopped trying to use bowlers who contain in favor of bowlers who try to get players out. In the lead up to the 2019 World Cup, England lucked out when they found Jofra Archer. Without Archer, England’s plan had been to used David Willey’s left arm medium-fast seam and swing and powerful tailender’s long handle. It would keep them competitive in high scoring ODIs. Archer gave them wicket taking heft which meant that their runs went further than they might have with an attack led by Willey.

England were unable to build an ODI attack around Archer and Adil Rashid. Archer’s injury problems didn’t help. But England’s problem since 2019 has been that they didn’t have a replacement for Archer or Liam Plunkett (96 wickets in 60 ODIs, more than 1.5 wickets per match). Australia, for instance, have built their attack around Adam Zampa (185 wickets in 110 ODIs) and Mitchel Starc (161 wickets in 86 ODIs since the 2015 World Cup). Pat Cummins and Josh Hazlewood collect more than 1.5 wickets per ODI. England have Adil Rashid (212 wickets in 144 ODIs), Jofra Archer (54 wickets in 31 ODIs), and Reece Topley (47 wickets in 30 ODIs). None of the others achieve 1.5 wickets per ODI.

Since the 2019 World Cup only Afghanistan, West Indies and Bangladesh have averaged fewer wickets per 50 overs in ODI cricket than England. Since the 2023 World Cup England have taken fewer wickets per 50 overs than any other ODI side. England and Pakistan have conceded 295 runs per 300 balls in this period, more than any other side.1

This inability to take wickets has meant that England’s runs don’t go as far as they used to. Add to this the fact that other teams are scoring quicker runs in general, and the advantage England acquired thanks to Morgan’s innovations after the 2015 World Cup has vanished.

England have been losing more often in recent years because the rest of the world has caught up, and in many cases, found ways to be even more efficient than Morgan’s innovations made England. To return to their cutting edge team of the late 2010s, England will have to find the balance to first match the efficiency of today’s best teams and then, if they can, do even better.

Figures for ODIs involving ENG, AUS, SA, WI, NZ, IND, PAK, SL, BAN and AFG only

As ever, the game evolves and there’s a first-mover advantage before the rest catch up. England changed the way the game was played between 2015 and 2019 but others have now emulated and surpassed them. Will be interesting to see what McCullum can do to make them cutting-edge again.